“Do you work out?”

“Yeah! I was sore for 7 days after my last session. It was such a good workout!”

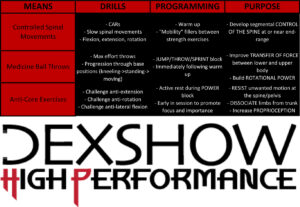

This interaction makes me cringe almost as much as a rounded back deadlift. Listen, I’m obviously a huge proponent of EXERCISE – it’s been shown to improve so many health markers I don’t even know where to start. Increased bone density and muscle mass, decreased cardiovascular risk factors, improved hormonal profiles, and improved quality of life are some of the undeniable benefits of exercise, not to mention other social benefits like sense of community, boosted self-confidence, and greater independence in older populations. I also greatly value RESISTANCE TRAINING, moreso than other forms of exercise, for the reasons I lay out HERE. Having been consistently in gyms and weight rooms for over half of my life, I’ve seen a lot of fitness trends come and go. I’ve been guilty of hopping on some of the bandwagons as well several times throughout my training career. When I was in high school, I walked to the gym everyday after school with my buddy and we worked out – at 14 years old, that means only doing exercises you like doing, with poor form and too much load, with no overarching plan or program. It wasn’t until I was afforded the opportunity to work with a coach that I began training. Granted, I was a high-level athlete who desired better performance, but it opened my eyes to a change in philosophy when it came to exercise. My trainer became my mentor and boss after my hockey career and I will forever be indebted to him for instilling an early love for strength and conditioning in me. In this article, I’ll shed some light on the differences between training and working out and why everyone, regardless of their goal, should spend more time training and less time working out.

TRAINING vs. WORKING OUT OVERVIEW

TRAINING

- Specific, measurable outcome goal

- Periodized program keeping the end goal in mind (microcycle, mesocycle, macrocycle)

- Adequate training split based on goals and training frequency

- Exercise selection relevant to the goal and progressed/regressed for current capacity

- Consistent inputs with enough volume for intended adaptation without interfering with daily function and/or sports performance

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to track improvements/gains

WORKING OUT

- No overarching theme or specific goal = “per day” programming

- Piecemeal exercise selection without any progression/regression model

- Inability to track results due to random exercises and excessive variability

- Not enough consistent exposure to a stimulus for intended adaptation

- Excessive volume in order to “crush” trainee leading to unnecessary muscle soreness and impaired daily function and/or sports performance

- No periodization/long-term plan

Let’s go over what I mean, starting with what I call WORKING OUT. Working out is what most people do for exercise. Set foot in a public Rec Centre weightroom, a big box membership gym, or most class-based facilities and you’ll find the majority of people working out. Not all, but most. I’ve been one of those people too, and fallen for the trap of needing to feel like I’m dying to feel like my workout was effective – it doesn’t work that way, and some people even do more harm than good, when searching for that feeling. Before I breakdown why working out isn’t the most effective, efficient, or best path to health, wellness, or performance goals, I’ll share some times that I think working out is beneficial. In the cases below, I’m referring to WORK OUTS that are random in nature but do not go overboard with amount of reps, total work, or intensity.

- Between Training Phases (for non-athletes)

- 1-4 weeks of unstructured, unplanned workouts can have a rejuvenating effect – mentally and physically – on many trainees who have been training consistently hard for several months of periodized training phases

- As Movement Play or Recovery

- Walking into an open gym and grabbing a single kettlebell to play with and explore your movement capacity and potential is fun and can reinvigorate a love for movement and training

- Making up a random bodyweight circuit can be a great recovery day for more advanced trainees without interfering with their structured training plan

- Post-Season for Elite Athletes

- After the rigid monotony and grind of a long season, many athletes would be wise to take a few weeks to a month off of their traditional off-season resistance program to recover from the season through unstructured training of exercises and modalities that they enjoy performing

With that in mind, let’s go over why I train my athletes and NOT work out with them.

I take tremendous pride in my training programs – the amount of time and thought put into a full hockey off-season would scare and shock many – and I shudder when I see people working out without any semblance of an over-arching theme or main goal. If anything, it seems like the main goal is to get destroyed, out of breath, and get as close to a heart attack as possible everyday.

“Lying in a crumpled heap at the end of workout seems like a badge of honour, but it is DEFINITELY not the most effective or efficient path to continued results.”

I try to educate my clients on this, especially when they are just starting an exercise program, as the common misconception in fitness seems to be that more is better and that if you don’t feel like you’re dying, you’re not doing anything. That’s simply untrue, and in many cases, counterproductive. Doing a different workout everyday for a month might seem like you are doing a lot, but this “per day” programming will not get anybody anywhere fast – it is too hard to track loads, skill progressions, and more importantly, know what/if any certain movement or exercise is CAUSING PAIN. Exercise programs should help mitigate the trainee’s chronic pain (if present) and certainly not cause or exacerbate pain.

Learning to regress and progress exercises and movement patterns was something that I struggled with when I first started coaching. I’ve lived in gyms since I was a teenager and have seen countless “trainers” and “coaches” struggle making an exercise look good with a client and have them perform it correctly. As a coach, you must be able to scale any exercise to match the preparedness, skill level, strength, and mobility of your trainee. This means having the skills and toolbox to change an exercise to suit the trainee, meet them where they’re at, and instill success/confidence in them while still garnering the intended adaptation of the exercise. Throughout the world, people in gyms fight with exercises that they’re made to perform, even if they don’t have the prerequisites. It doesn’t have to be that way. Much of the problem stems from inadequate programming but a good coach should also be able to modify an exercise on the fly if the variation does not fit well with how their client feels while performing it.

Speaking of variation, excessive variation of exercises and performing “Instagram Exercises” (random exercises that look ‘cool’) for the sake of novelty IS NOT an efficient way to garner results. For example, if you’re performing 50+ different exercise variations every week that constantly change weekly, you are most likely unable to:

- Track performance in the exercises (load, volume, proficiency)

- Accumulate enough total volume (reps) of any variation to elicit an adaptation, which is the purpose of training

- Progressively overload the exercises adequately

Recover from so many different movements enough to be able to make gains in strength, power, endurance, or other qualities over the course of a training cycle

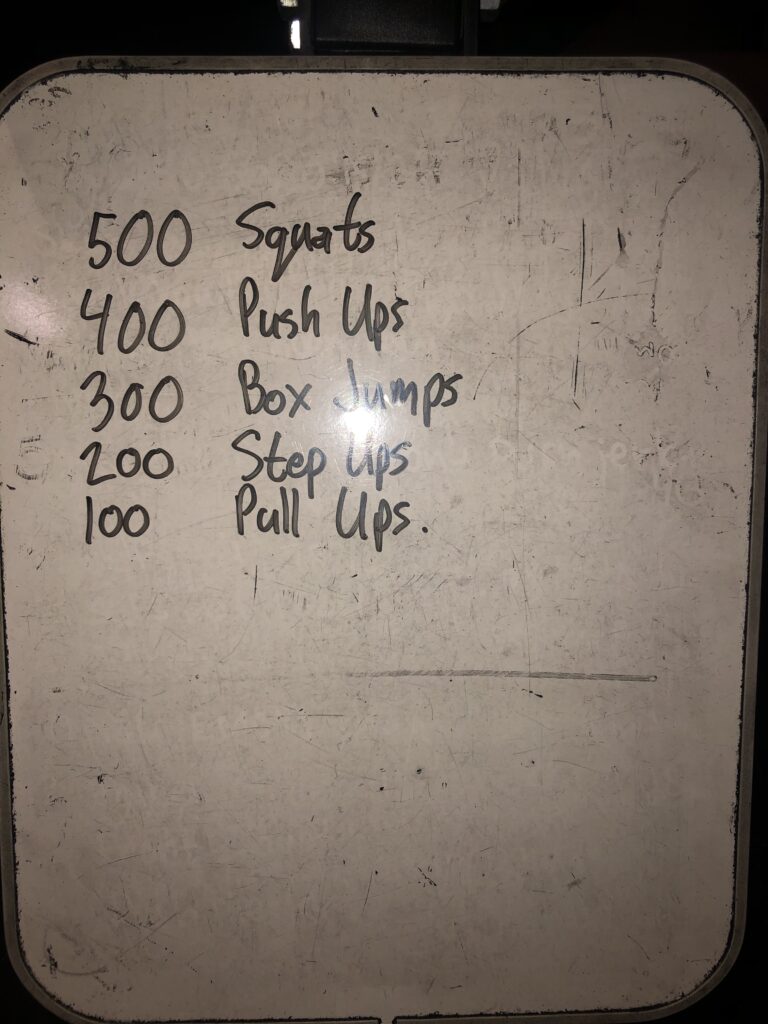

Another thing that is common in “work out programs” is the misguided need or want of extreme muscle soreness – usually due to the inordinate amount of reps/volume OR the excessive variation described above. I’m not saying muscle soreness is necessarily bad in all cases, but MUSCLE SORENESS DOES NOT INDICATE AN EFFECTIVE TRAINING SESSION. This needs to be shouted from the mountain tops. Being sore sometimes is fine, and probably inevitable if you push the boundaries of performance, but being chronically sore affects future exercise bouts, changes subsequent movement quality, and can greatly influence quality of life or on-field performance of athletes. Not being able to sit down on the toilet for 5 days after you did 500 squats is not very fun, and it’s not an effective strategy for long term health and fitness changes. If this is you, you’re working out and you’re not training. Beware the “coaches” or “trainers” who take pride in making their trainees sore for a week – to me, that’s a tell-tale sign that they don’t know what they’re doing.

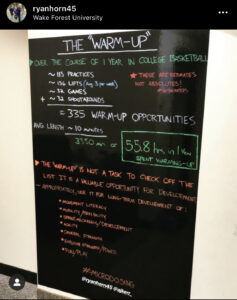

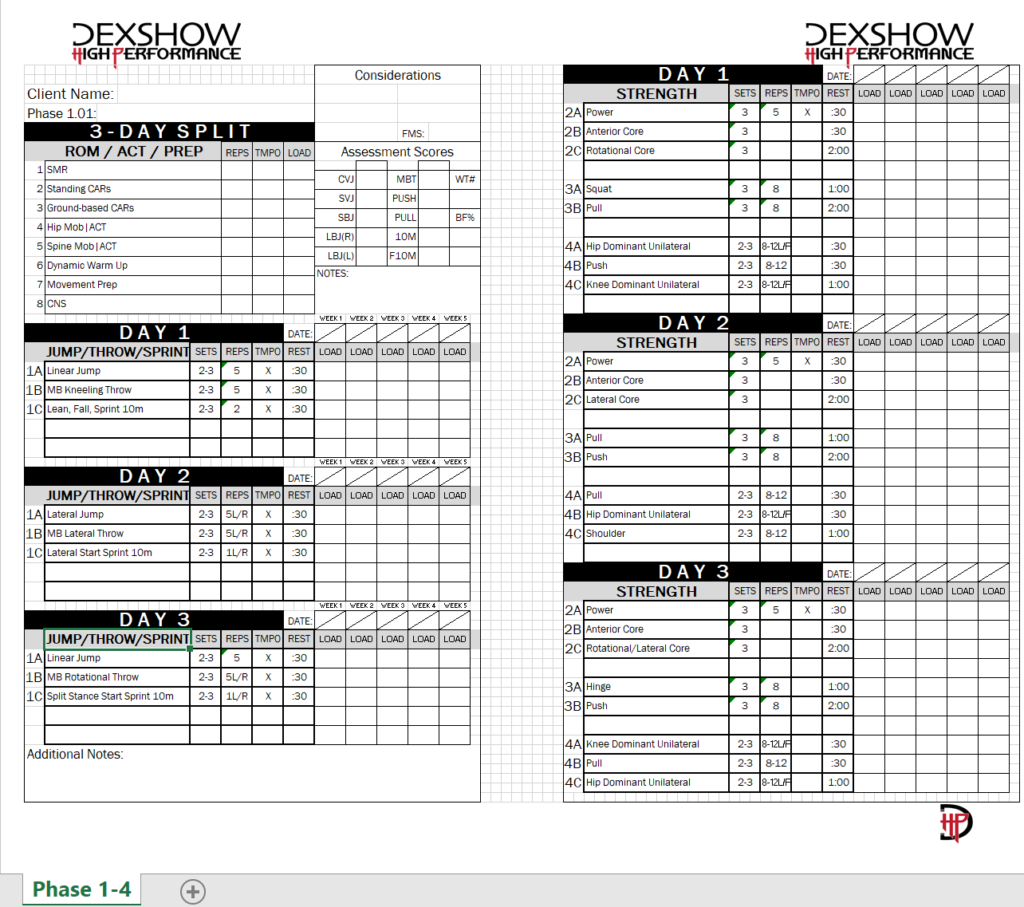

The last piece of working out vs. training that I want to discuss is PERIODIZATION. Periodization is the concept of layering training phases over a time period that allows the trainee to “stack” the adaptations acquired during a training phase with each subsequent phase to realize the full potential of the program. There are a lot of periodization models and most folks will benefit from most of them when implemented correctly. Linear, Undulating, Concurrent, Conjugate, and Triphasic are all periodization models that share the traits of a solid TRAINING PROGRAM. Periodization models need to be organized by microcyle, mesocycle, and macrocycle.

A MICROCYCLE is the narrow-focus view of the training program – I use a week as my base timeline for my programs. Planning a training week comes down to how frequently the trainee trains over 7 days and then I can break down what goes in to each session. If I train an individual once per week, they will have a whole-body session that is comprised of both upper and lower body exercises. In fact, I’ll also employ whole-body splits for 2- and sometimes 3-day training weeks. If I see someone 4 or more times per week, I’ll usually split their sessions into upper and lower body days.

A MESOCYCLE is an entire training phase that is comprised of 3-8 weeks of the microcyle. For most of my trainees, I like using a 5-week mesocycle to ensure that there is enough exposure to the exercises to elicit a change, adequate time for progressive overload, and the timeline is short enough to keep training relatively fresh. For many of my off-season hockey players, mesocycles last 3-4 weeks – these are also some of my more frequent trainees so they are getting more variety throughout their training week than someone who trains once per week.

Continuing to zoom out on the periodization of a training program, we have the MACROCYCLE. This is the entire timeline of training – it could be a full calendar year, or for my off-season hockey players, it is usually 3-4 months as they then return to their respective teams for the season. The ultimate goal of any training program is to have the trainee realize their full potential (performance goals, body composition change, weight gain/loss, etc.) at the end of the macrocycle. It is all planned. Random exercises, random set and rep schemes, and random tempos are all indicators of working out NOT training.

CONCLUSION

Training trumps working out in the long-term every time, and that doesn’t just go for 1:1 personal training. Class-based fitness should revolve around a periodization model that suits the goals of the majority of the trainees – results will be better and more sustainable. The use of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) can help individuals track their progress. If you’ve never repeated the same microcycle for several weeks, haven’t tested and retested a KPI, or haven’t seen the progress you’re looking for, you’re working out and not training.

Do you train or do you work out?

Get strong, stay strong.

Coach Dex